In the sound garden

In the sound garden

by Chris Johnston

Herb Jercher of Sunshine is a "sound sculptor" and part�time ratbag art activist. He was one of those partly responsible for covering the bronze Willlem de Kooning Standing Figure sculpture at RMIT in a cage last year, amid much outcry.

At the moment he's trying to promote the idea of sonically enhanced children's playparks (swings and slides that "sing") in his beloved western suburbs without a lot of joy, despite helping build Melbourne's first sound playground in Brunswick many years ago. He plays guitar in Barry Veith's contemporary big band and makes thrilling musical instruments from indistinct, unusual found objects.

Jercher is the kind of enlightened man who can derive hours of unfeasible joy from watching raindrops fall into his swimming pool.

His back yard is a suburban installation of sound and vision. It adjoins a property belonging to Christine Babinskas; hers too is a back yard enriched by creativity and imagination. Babinskas, a dancer, recently used it to present her thesis in dance. It was entitled Perception of Dance of Perception � the paving stones played musical notes as the examiners trod wearily across them. Their two housed are linked by gangplanks and their back yards are simultaneously bizarre and beautiful.

Near Jercher's backyard workshop is a giant sandpit. He plays in here with his son Skete, 8, and daughter Karma, 13. The pit is covered by a tarpaulin to shield it from the elements an even has a lightbulb for night work.

"I love sandpit therapy," says Jercher, 50. "How many dads are out in the sandpit with their kids? I love making 'brrm brrm' sounds when you play aeroplanes. I'm up to nine different 'brrm brrms' now. I love it." "You haven't forgotten how to play," adds Babinskas. "That's your charm."

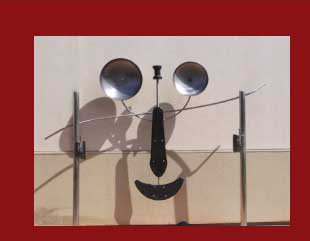

Most of this unique twin-backyard installation has a sound component fashioned by Jercher, who has worked as a performance artist, sound consultant and composer.

An imposing public address speaker is a kind of centerpiece; it acts as an echo chamber for the birds that land in it on the way elsewhere. Off almost every branch of an apple tree hangs soundtape, which buzzes in the wind, and found objects � an emerald green railway reflector, a horse bit, a rusty industrial bolt � dangle from the ends. The different weights cause the lengths of tape to vibrate differently. To stand underneath the tree is to be immersed in a dozen mystery frequencies from thin air.

There's a musical outdoor table. Jercher beats it with a mallet and grins. The steps to the door also make an abstract music. "You hear it?" he asks. "Its microtonal but it's there. I call it inverted ascension. The pitch goes up as you go down."

There's an ambiance to this place. The sounds blend with their environment. The imposed sounds become the environment.

It's not just hanging chimes, although there are plenty of them, in wild mutations. Jercher also has his wind cutters, huge bamboo bows that he swishes dramatically through the air to make tones.

And he has a towering pink plumbing tube standing on the corner of the vegetable patch. Put your ear to the opening and it's like seashells at the seashore magnified by 10. Through it you can hear the whole world turning, if you listen receptively enough.

"Sound is my axis," says Jercher. "It's my method of expression. I can code sound as a language, and I can communicate. There's nothing you can do on God's earth that doesn't make a sound. Sound is fundamental to existence."

But although these adjoining back yards are artful, they are also chaotic. The bits and pieces in them are there to be weathered, to be affected, and to be moved around at random.

Around here, decay and chance are all part of the game. The ten �pin bowling ball on a stick may not be covered in a kitchen steamer tomorrow. The discarded chairs attached to lawnmowers move around spluttering without cutting the grass.

There's a mobile shed that was once a Toyota engine packing case. Within it Jercher is designing a geodesic dome. An old brandy barrel nestled at the bottom of a eucalyptus tree is yet another kids' hiding place. It has carped inside and an ornate porcelain doorknob; do whatever you wish within it. Nestled in the grass is a little white ammunition box. It holds the bone-white skulls of a fox, a goat, a sheep and a wombat.

"When we have a party for the kids, it isn't McDonald's," says Jercher. "They come out and muck about. It's a discovery environment. They rearrange things. Nothing remains precious. You have to a accept that things sit naturally, nature takes over."

He says if no one ever sees these back yards it doesn't matter because they're still art. He says he doesn't need anyone else to tell him he's already living in heaven.

"It's about zones of contemplation, and about manipulating materials and found objects, and about playing. They are staging places for ideas. You can stand here and block the world out. The smells, the sounds, the sights�you are looking at an environment that is about interactive sensory perceptions. I once called them environmental ballistic intrusions. This is the way I perceive my world."

1. This article first appeared in

the Age

, Monday 30 June 1997 as

Backyard obsessions: Sculpting noise

(Metro C4).

It is reproduced here with kind permission from the Age.